Climate litigation IS ALSO about biodiversity

by Jacob Phelps, co-founder of Conservation-Litigation.org

Climate litigation globally has focused on pushing companies and public institutions to strengthen their efforts to cut greenhouse gas emissions. In a small number of cases, litigation has also held offenders legally and financially responsible for the harm they cause to the climate. However, like the broader climate change mitigation movement, climate litigation risks decoupling itself from the rest of nature – notably the biodiversity that underpins all ecosystems.

Indeed, in preparation for the UN Biodiversity Cop16 in Colombia, the country’s Environment Minister and CoP President, Susana Muhamad, highlighted that ‘just cutting carbon emissions will not prevent climate breakdown’.

In our work at Conservation-Litigation.org, we often face this climate-biodiversity disconnect. We have heard multiple times that donors “will fund climate litigation, but not litigation focused on nature or biodiversity”.

Climate litigation is also about biodiversity.

There is growing recognition that long-term climate stability relies on functioning ecosystems.

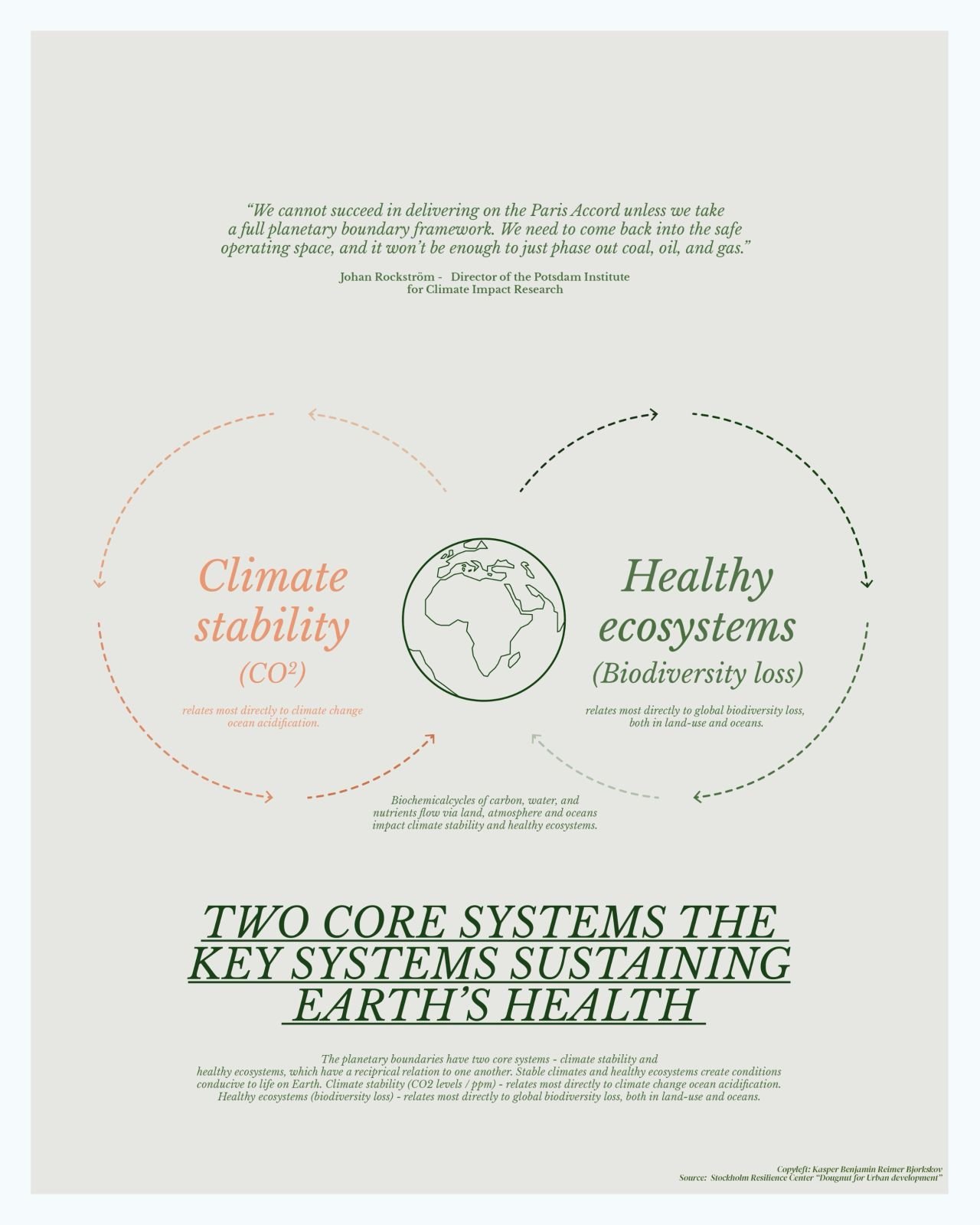

The Stockholm Resilience Center recently wrote that the planetary boundaries have two interconnected core systems - climate stability and healthy ecosystems, which have a reciprocal relationship to one another and are both necessary to life on Earth.

I recently wrote a report for the UNODC about the links between biodiversity loss and climate risks – links that, although often complex, long-term and nonlinear, are undeniable.

These relationships can also be reflected in climate litigation. Its active links to biodiversity are perhaps most apparent in cases against those who harm habitats such as tropical forests, peatlands and seagrass beds - habitats that not only store significant carbon stocks, but are also important to biodiversity and human communities.

In these cases, climate, biodiversity and human rights litigation can geographically co-occur, often share drivers, have ecological links, and are not mutually exclusive: For example, felling and burning trees to clear land for agriculture simultaneously harms:

Biodiversity (e.g., the trees themselves and species that rely on them);

Human communities that use and value the site (e.g., livelihoods, sense of place, culture); and

Climate (e.g., emissions from burning vegetation, loss of future carbon sequestration by the trees, reduced long-term ecosystem stability that allows it to deliver carbon services).

Instead of viewing these as separate strands of litigation, future cases should consider whether to integrate them to better reflect the realities on the ground.

A key example from Brazil

In June 2024, a Brazilian court ordered a cattle rancher to pay US$50 million in climate compensation to the National Climate Emergency Fund for illegally deforesting 5,600 hectares of public land. Importantly, the civil suit recognised that clearing land for agriculture had cascading impacts on climate, and that the offender could be held accountable for those impacts.

However, this case largely overlooked that the Brazilian Amazon is also globally among the most important regions for biodiversity conservation and intact forest landscapes – key to the survival of threatened species such as the jaguar, giant anteater and giant armadillo.

Moreover, these public lands have a number of other values to society, including cultural, scientific and intrinsic values that are important to local communities and to society.

It is essential that such climate litigation also recognises these broader, non-climate impacts. This is key because these other dimensions of harm will also require mitigation and adaptation actions that must be secured through litigation. Payments to the National Climate Emergency Fund are important, but will not help recover biodiversity loss, heal cultural harm or restore public trust. Recognising these diverse values and impacts in court is important to educating offenders, decision-makers and the public. To the contrary, it is a mistake for prosecutors and judges to label forests as only or primarily valuable for their carbon services.

Unifying litigation strategies

In many jurisdictions, the legal pathways that enable litigation for harm to biodiversity, human rights, climate and the broader environment are separate. For example, climate litigation is often separate from broader environmental protection and liability provisions (i.e. Indonesia), and harm to wildlife is treated as distinct from harm to habitat (e.g., India). There are also differences in approaches to litigation, often intentionally distinguishing ecocentric from anthropocentric cases.

From both an ecological and justice standpoint, such distinctions are artificial, the legacies of disjunct incrementalism in policy and practice over time. Harm to climate is also harmful to biodiversity and human communities. Harm to biodiversity has cascading impacts on climate and humans. Cases involving harm to humans often also involve harm to the environment.

Fortunately, at least in some countries, including Brazil, Indonesia, Liberia, there is clear scope for litigation that responds to the multiple types of harm, with cases integrating climate and biodiversity, ecocentric and anthropocentric harm. Moreover, many countries enshrine broad rights to a clean environment, without distinguishing between climate, water, biodiversity, etc. Although legislation and litigation strategies will continue to differ, it will be important to see how environmental litigation can better reflect the breadth, science and experience of environmental harm on the ground.